Director of the SDGs Future Investment Research Institute, Akira Aoyama interviews Oriza Hirata

Multi-award-winning playwright and director, Professor Oriza Hirata is arguably one of preeminent figures in Japanese theater of this past century. Since establishing his Seinendan theater troupe to further explore his pioneering “contemporary colloquial” genre of naturalistic performance in the early 80s, Hirata’s work has been premiered around the world to rousing acclaim. He has been invited on numerous occasions to collaborate not just with leading performing arts houses overseas but also on interdisciplinary projects including a hybrid human and robot comedy piece with the assistance of leading robotics researcher Dr. Hiroshi Ishiguro.

Needless to say, creative expression through the performing arts is fundamental to our culture and enriches people’s lives, and Hirata has long been an advocate for performing arts education which he feels has been lacking in Japan.

This is the second instalment in a three-part interview. See part one here.

Akira Aoyama: Society is the birthplace of culture, but what do we call that society in the first place? You have land, nature, and local communities. Perhaps it is most pertinent to talk about society’s connection to land. Incidentally, where were you born, Hirata-sensei?

Oriza Hirata: I was born in Komaba, right by the University of Tokyo. It’s an uptown area, but it’s still Tokyo, and I grew up in the middle of this shopping street. It was the 50s and 60s, a time when it was normal to leave your children alone at home, which was also the case for me. The kindergarten that I went to was a lively place, where events and plays were frequent occurrences, and my father, a struggling writer, was also doing a little theatre, so I was constantly exposed to the world of movies and performing arts growing up.

It makes sense, that you were engaged with theatre from such a young age.

That’s right. My father raised me to be a writer, and I intended to pursue writing. But then I went to university, and that’s actually when I started acting.

You undertook a round-the-world cycling trip before university, at around the age of 16, didn’t you?

That was such a long time ago that I no longer remember why I did it. But going back to Komaba, it was a relaxed place on the one hand, but it is also the area immediately outside the University of Tokyo’s main entrance, the Faculty of Liberal Arts to be precise…the prevailing attitude among locals here is to ensure that children with good grades should be go to the University. And I think as a child—especially as it was an even more competitive society back then—this weighed heavily on your heart. So once in middle school I elected to attend a part-time high school, and after a year going there, saving money, I took two years off to cycle around the world.

Why a world trip?

Well, I think I probably wanted to go abroad. It wasn’t a time when high school students could travel freely as they do now, and in any case I simply wanted to go.

That must have been thrilling, and with so much going on…

It was.

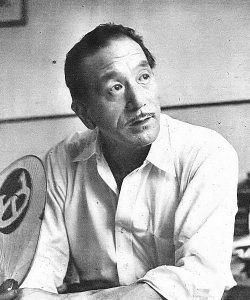

Yasujiro Ozu was a major influence on Oriza Hirata

After that, you went to the International Christian University, and you wanted to perform there, but was the role at ICU a significant one?

I think it was a big deal. The university has a very laissez-faire spirit and so I wrote a script myself, brought together a bunch of students who were bunking off class as well as those hanging around in the student lounge, and formed a troupe.

When it comes to theatre in Japan, it is Western culture; a foreign transplant, much like science and other modern developments that we imported, isn’t it? But you wanted to take an approach to theatre that was based upon the Japanese language, the Japanese way of life, Japanese thought. At what point did you resolve to do this?

Originally I began doing theatre because of my interest in language, but I studied abroad in Korea, with the rationale that it would be better to learn a language like Korean that has strong grammatical similarities to Japanese. In the process of learning it and seeing just how similar it was structurally, I was able to look at Japanese language more objectively, and I thought the reason why I had felt such a sense of discord when it came the language of theatre was because, in short, these European acting methods were imported wholesale, right down to way the scripts were written and the choice of wording, and it is simply not how Japanese people speak. After that I began to theorize about whether it a problem with word order, particles, auxiliary verbs and so on.

In that case, it was not just about Japanese language but the way Japanese think and the way of life as well?

Yes, of course there is that too. In the beginning I enjoyed Yasujiro Ozu’s films and wanted to transcribe that world into a play, and I was thinking about how to achieve that at the time, while in my twenties.

Recently I heard about a play called Tokyo Note performed in Toyooka that takes place in seven languages, but by contrast, it’s really about how important and interesting languages are.

That’s right. One of them—and this is the same with Ozu’s films as well—that out of something extremely Japanese, some kind of universal quality will emerge from it. That is perhaps because the acting is less imitation than a genuine pursuit of Japanese people’s peculiarities or uniqueness, but in that you can say culture is being transposed into the realm of art and when we enter the realm of art everything becomes universal and understandable by many different people at once.